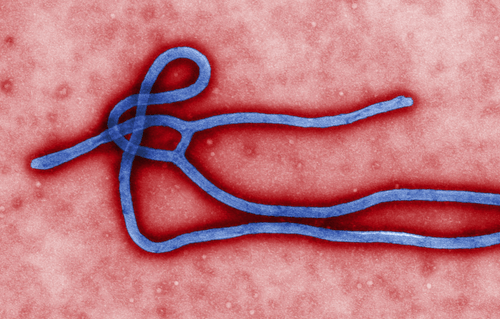

Wikimedia

The CDC has just confirmed the very first case of Ebola in the United States. A still unnamed man is believed to have traveled from West Africa to Dallas; doctors say he possessed no symptoms when he first flew into the good 'ol US of A, but five days later, all the tell-tale signs were there.

While local health officials have systematically begun identifying close contacts of the infected mystery man in order to monitor their health for the next 21 days following potential exposure, the CDC insists that those who flew to Texas with the patient are not at risk as Ebola is only contagious if someone is experiencing "active symptoms." (Like chronic headache, muscle pain, diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, or unexplained bruising or bleeding.)

While the CDC insists that the risk for an outbreak in the U.S. is "very low," they also explain that the 2014 Ebola outbreak is the largest in history and marks the very first Ebola epidemic the world has ever known.

And indeed, the numbers are staggering; according to the World Health Organization, the Ebola virus has infected 6,553 people and killed 3,083 across the three countries hit hardest: Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Despite grueling efforts by dedicated doctors and non-profits, the number of cases has been doubling every three weeks in Liberia and every month in Sierra Leone and Guinea. The CDC believes the infection rate could rise to 1.4 million people by January, "without additional interventions or changes in community behavior."

Currently there are no approved vaccines or treatments for Ebola, so the protocol for "treatment"—aside from simply isolating the infected from others—is as follows:

- Providing intravenous fluids (IV) and balancing electrolytes (body salts)

- Maintaining oxygen status and blood pressure

- Treating other infections if they occur

The CDC says there are two experimental treatments currently being developed for Ebola that are coming down the pipeline—they've been been tested and proven effective in animals, but have not yet been tested on humans in randomized trials.

One of them, however—ZMapp—was administered to two American missionaries, Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, who were infected while working in Liberia. And while nothing is confirmed, it's believed the treatment may have been responsible for saving their lives.

Previously only tested on monkeys, ZMapp works like this: Three mice are exposed to fragments of the Ebola virus, which force their bodies to develop antibodies; doctors then harvest said antibodies within the mice's blood to create the medicine.

A third American, Dr. Rick Sacra, was also snatched from the jaws of death with the other experimental drug, TKM-Ebola, which inhibits the virus’s ability to replicate. Sacra was additionally treated with plasma from Dr. Kent Brantly.

While the medical community is obviously waiting with bated breath to see the drugs formally go through the FDA rounds, Doctors Without Borders urges caution and not to abuse the "compassionate use" regulation:

"It is important to keep in mind that a large-scale provision of treatments and vaccines that are in very early stages of development has a series of scientific and ethical implications. As doctors, trying an untested drug on patients is a very difficult choice since our first priority is to do no harm, and we would not be sure that the experimental treatment would do more harm than good."

Not surprisingly, capitalism waits for no man: The two companies developing ZMapp and TKM—Tekmira Pharmaceuticals and Sarepta Therapeutics—have leapt up the NASDAQ 25% and 7%, respectively, in the wake of the U.S. diagnosis.

Also, am I the only one who's disturbed by the fact that three Americans were deemed important enough to try and save with experimental—albeit maybe very dangerous—treatments, while hundreds of thousands of West Africans are left with little hope other than to die swiftly?

Nope. In fact, conspiracy theories abound. Some people believe the government is in full possession of a cure but has no plans on dispersing it among the ailing Africans, while others believe the CDC—suspiciously—has only "proven" the vaccine to work on white people, blaming the higher levels of melanin in black skin as the culprit.

Conspiracy theorizing aside, the impacts of this devastating virus remain all-too-real.